Boys at her school shared AI-generated, nude images of her; She was expelled not them. Is this the school’s fault?

By: John Huber MarylandK12.com

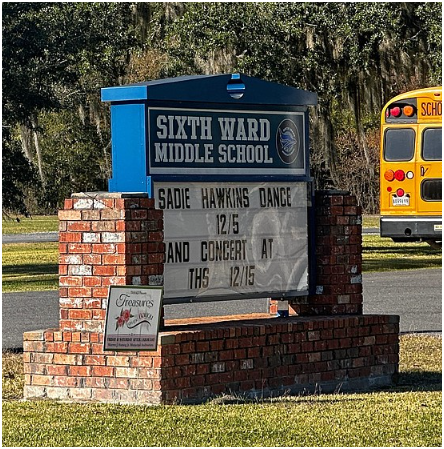

Just before Christmas, a 13-year-old girl at a Louisiana middle school found herself at the center of a nightmare. AI-generated nude images of her and her friends began circulating among classmates. The pictures were fake, but the humiliation was real. They spread quickly on Snapchat, a platform where content disappears almost as soon as it is viewed. By the time adults were alerted, the images were gone. The principal even questioned whether they had ever existed.

The girl, overwhelmed by taunts and rumors, lashed out on the school bus. She attacked a boy she believed was involved. The school expelled her for more than ten weeks and placed her in an alternative program. Later, law enforcement charged two boys under Louisiana’s new law against AI-generated sexual content. The school punished what it could confirm, which was the fight, not the digital harassment it could not verify.

This story matters for Maryland. These types of situations occur in our schools every day. They do not always involve AI-generated images. Often, they are simpler but equally damaging forms of harassment, such as cruel messages, embarrassing photos, or relentless rumors spread through social media. The technology may change, but the pattern is the same: a student becomes the target of humiliation, and the school is expected to intervene. Parents want immediate answers and accountability, yet schools face the same limits whether the harm comes from an advanced AI tool or a basic text message. They cannot investigate private devices, they cannot confirm what they cannot see, and they cannot share disciplinary details with anyone but the student’s parents. These realities make it clear that the challenge is about the growing complexity of student interactions in a digital world and the unrealistic expectation that schools can police every corner of it.

Schools exist to educate and maintain order, not to conduct criminal investigations. Their training and certification do not include digital forensics or law enforcement procedures. When a fight breaks out, they can act because they can see it and confirm it. When a crime occurs online, they must refer it to law enforcement. That is the boundary. Yet parents understandably become frustrated. If your child is victimized, you want justice. But for every victim, there is another parent insisting their child did nothing wrong. Schools cannot share details about other students’ discipline because federal privacy laws forbid it. This silence often looks like indifference, even when schools are doing everything they are allowed to do.

There is another hard truth. Schools cannot excuse retaliation, even when it feels justified. Two wrongs do not make a right. When a student fights back physically, that act still violates school rules. Maryland’s discipline philosophy emphasizes restorative practices, but those practices begin after the disruption is addressed. Safety and order come first.

So, what can schools do? They can respond to what they can confirm, such as physical altercations. They can report suspected crimes immediately to law enforcement. They can provide counseling and emotional support for victims. They can teach students about digital ethics and the consequences of misusing technology. And they can communicate clearly with parents about what is possible and what is not. Schools cannot investigate deleted snaps. They cannot seize phones without consent or a warrant. They cannot share another student’s punishment with anyone but that student’s parents.

Parents have a role too. They can preserve evidence by taking screenshots before content disappears. They can file police reports when crimes like deepfake exploitation occur. They can ask schools about digital safety programs and cell phone policies. And they can understand that privacy laws limit what schools can disclose.

Maryland law already addresses some of these issues. Grace’s Law makes electronic harassment of minors a crime, even a single significant act. Senate Bill 360, passed in 2025, expands protections against non-consensual intimate images, including AI-generated deepfakes. Federal privacy rules, mirrored in Maryland, prohibit schools from sharing details about other students’ discipline. These laws matter because they define what schools can and cannot do.

The Louisiana case is a warning. Technology has created new ways to harm children, and those harms move faster than policies can keep up. Schools cannot chase disappearing images or run forensic exams. They can keep classrooms safe, teach kids about digital ethics, and work with law enforcement when crimes occur. The solution is not to blame schools for failing to do what they were never designed to do. The solution is partnership. Parents, police, and educators must work together to protect children in a world where harm can be created with a click.

Dig Deeper With Our Longreads

Newsletter Sign up to get our best longform features, investigations, and thought-provoking essays, in your inbox every Sunday.

The MEN was founded by John Huber in the fall of 2020. It was founded to provide a platform for expert opinion and commentary on current issues that directly or indirectly affect education. All opinions are valued and accepted providing they are expressed in a professional manner. The Maryland Education Network consists of Blogs, Videos, and other interaction among the K-12 community.