Part 3: The Abby Zwerner Case—Why a Missing Reinstatement Conference Matters and What Else Went Wrong

In this third installment on the Abby Zwerner case, we look at this event in a little more detail and uncover some more gaps. The first article outlined the events surrounding the shooting, and the second article, “The Abby Zwerner Case and The Authority Gap,” explored why teachers could not act and why the defense arguments fell short. In this article, we focus on one deceptively small but very important question: why was there no reinstatement conference or behavioral plan when the student returned from suspension. We also look at the related failures that compounded risk on the day Zwerner was shot.

When a student is suspended from school, it is standard practice to conduct a reinstatement conference. Some schools absolutely require it. The theory behind a suspension is simple. Students who are suspended have committed an act or series of acts that are so disruptive to the learning environment that they need to be removed. The removal lasts until a conference is held with the administrator, parent, and child, and the child agrees to make changes. The child should agree to these changes as a condition of reinstatement. In most cases, the student is given a reinstatement form that he carries to all his classes to let his teachers know that the administrator has met with the student and his parent(s) and that the student has been reinstated. At least that is how it is supposed to work.

When these conferences are done properly, they help reset expectations, confirm services, and rebuild trust after serious misconduct. In the lead-up to January 6, 2023, there is no evidence of a formal re-entry conference for the child who had been suspended before returning to Richneck Elementary. The special grand jury’s published account does not include any such meeting and reporting that synthesized the document does not identify one either.

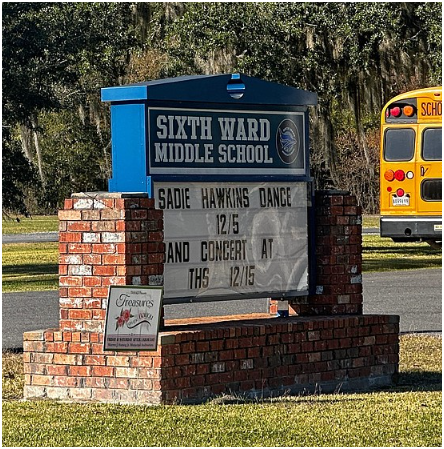

This little bit of information is significant when one looks at the sequence of events. The day of the incident was the same day he returned from suspension. The incident that led to the suspension included him throwing and breaking Ms. Zwerner’s phone. This was an aggressive act directed specifically at Ms. Zwerner herself.

This student was obviously harboring serious anger and aggression toward Ms. Zwerner, and it was not addressed. In fact, not holding such a conference allowed it to fester even more. The purpose of such conferences is to address any lingering animosities like this.

The absence of a structured re-entry matters because this student did not arrive in a vacuum. He arrived that day with anger and destruction on his mind, and it was directed at one person. In addition to the cell phone act directed toward Ms. Zwerner, there are multiple accounts of prior incidents describing a pattern of aggression and disruption, including choking a teacher and chasing classmates with a belt, details that appear throughout media coverage synthesized from the grand jury record and court filings.

These are the kinds of red flags that require concrete planning, adult supervision structures, and documentation so supports are not left to chance.

As the day unfolded, staff attention was focused on make-up testing, a point that surfaced repeatedly in civil trial reporting. Jurors later found former assistant principal Ebony Parker grossly negligent, with coverage noting testimony about the school’s testing focus and the sequence of ignored warnings.

The special grand jury offered precise language that helps parents and teachers understand how warnings accumulated without decisive action. The report recounted that “over the course of approximately two hours, Dr. Parker acted in complete disregard for the safety of all the children in Ms. Zwerner’s class,” describing four distinct warnings that a gun might be present and stating that Parker “neglected to take any action upon receiving four reports of a potentially dangerous threat.”

The grand jury also described the stakes in stark terms. It wrote, “Had this been an active shooter situation, the unaddressed security issues at Richneck for the 2022–2023 school year would not have only guaranteed possible success, it would have guaranteed a probable massacre,” pointing to broken emergency buttons, inconsistent training, and gaps in communications equipment.

Multiple moments in the timeline are important for understanding the confusion and delay. Reporting on the grand jury’s chronology notes that a teacher told Parker that two students said the child had a gun in his backpack around midday, then returned to say a backpack search had not found the weapon, then texted that the child had “put something in his pocket,” while a counselor later asked to search the child and was refused. After the shot, another child reportedly told a teacher, “I told you. I tried to keep you safe. I told you.” A plea that reads like a small child’s attempt at crisis prevention in a school where adults did not act quickly enough.

Parents will reasonably ask what was happening in the main office while the classroom crisis escalated. The report describes that Parker “locked herself in her office” after learning someone had been shot and that the principal had closed her own office door while Zwerner collapsed nearby.

The question of parent communication is another unresolved gap. Throughout trial reporting, Parker is said to have claimed “the mother was on the way,” yet the public record summarized in news coverage does not establish that she herself called the mother prior to the shooting or clarify what was actually said. One statement attributed to Parker was “tell her [Zwerner] she can call the child’s mom to come get him,” a line that suggests reliance on an indirect message rather than a direct administrative call.

The file management story is equally troubling and sits at the heart of why re-entry routines matter. Investigators executed search warrants for the child’s academic file and found that one copy was at the home or in the car of a central office leader, with disciplinary records missing, while the second copy allegedly kept at the school was never located.

The split between testing tasks and safety escalation is the line that parents and teachers cannot ignore. Warnings accumulated, but the building did not move to lockdown or to a principal-authorized search before the shot was fired. Teachers and counselors were blocked from searching, even as concerns about a gun became more specific.

There are two more details from the grand jury’s account that clarify how close the school came to a larger tragedy. The report says the gun had “seven additional bullets ready to fire if not for the firearm jamming,” a mechanical failure that prevented further shots when the child attempted to fire again without changing his facial expression. And prosecutors publicly said that the report was “thorough” and “brutally honest,” promising continued investigation into missing files and other matters.

Parents and teachers deserve a clear answer to the central question. A reinstatement conference is a small meeting with oversized consequences. When done properly as required, it provides a plan for a child who has already demonstrated risk, documents who will do what, and sets conditions for return that signal safety comes first. Without it, routines become improvisation. The events of January 6 show what improvisation looks like in a school that was already struggling with emergency systems and communication. The special grand jury’s report and the civil trial reporting make that story plain.

Would a reinstatement conference have prevented this tragedy?

The honest answer is that no single meeting can erase or prevent risk. A reinstatement conference is not a magic shield. It cannot guarantee that a child will comply, nor can it eliminate every danger. But its absence tells us something deeper about how systems fail when structure gives way to improvisation.

The child who shot Abby Zwerner had just returned from suspension. He had a documented history of aggression including choking a teacher, chasing classmates with a belt, and cursing at staff. These behaviors should have triggered some kind of behavioral plan or student support plan and a conversation about the safety of all around. Instead, there is no evidence that such a meeting or discussion occurred. The special grand jury report makes no mention of it, and trial testimony never established that one took place.

Would that meeting have stopped the shooting? Maybe not. But it would have forced adults to confront the risk openly, document expectations, and confront the obvious anger this student felt specifically for Ms. Zwerner. Without it, the day unfolded in fragments: warnings ignored, searches denied, no lockdown, and no 911 call until after Zwerner was shot. The grand jury’s language was blunt: “Over the course of approximately two hours, Dr. Parker acted in complete disregard for the safety of all the children in Ms. Zwerner’s class.”

That is not just about one administrator; it is about a school with a culture that lacked urgency and clarity.

Even if a conference had happened, it would not have mattered without follow-through. A plan on paper means nothing if testing priorities overshadow safety. The report warned that broken emergency systems and poor communication “would have guaranteed a probable massacre” in an active shooter scenario. That is the real lesson: safety cannot hinge on one meeting. It must live in routines, authority structures, and a culture where warnings trigger action.

So where does that leave us? Not with a call for more paperwork, but with a demand for more preparedness. Parents and teachers should ask hard questions now: What happens when a suspended student returns? Who owns the plan? How do warnings move from whispers to lockdown? These questions are not hypothetical. They are the difference between a school that improvises and a school that protects.

Again, this tragedy is not about one administrator. It is about a school with a culture of laziness and no attention to detail. Laziness allowed the child to return with no conference. It is not just about not prioritizing safety either. It is about a school and system that had a culture of allowing multiple issues to go unaddressed. A culture that permitted several safety and security issues to go unaddressed for some time. A culture that seemed to think it was not appropriate to interrupt the principal in a meeting and tell her that there were reports that a student had a gun.

So, who is responsible for this culture? The Superintendent and the Principal. They were both granted immunity while Dr. Parker was effectively abandoned.

We will look at the immunity issue in the next part of the series

Dig Deeper With Our Longreads

Newsletter Sign up to get our best longform features, investigations, and thought-provoking essays, in your inbox every Sunday.

The MEN was founded by John Huber in the fall of 2020. It was founded to provide a platform for expert opinion and commentary on current issues that directly or indirectly affect education. All opinions are valued and accepted providing they are expressed in a professional manner. The Maryland Education Network consists of Blogs, Videos, and other interaction among the K-12 community.